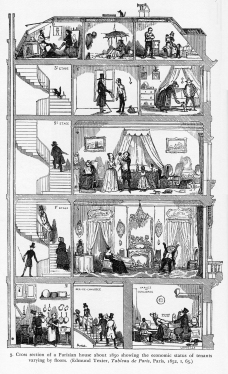

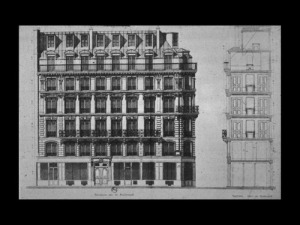

1852 Paris apartment building. Cross-section image, showing apartment hierarchy. Edmund Texier ‘Tableau de Paris’ 1852, 1, 65. http://architokyo.wordpress.com/exposition/

Just as place shapes people, people shape place. In the case of nineteenth century Paris, people had been shaping the urban environment for centuries; people, that is groups, classes. In the late nineteenth century Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann and Napoleon the Third changed Paris completely. The affects that those changes had upon class relations altered the way people lived forever. Not only were working class homes ripped down, but they were replaced with dwellings completely different to what the working classes of Paris had ever known before. It is important to understand the bourgeoisie opinion of the working class before it can be understood why two bourgeois men would change the lives of thousands without consultation.

The working classes of Paris during the nineteenth century were regarded as the “dangerous classes” and “labouring classes” these two groups were virtually indistinguishable to the bourgeois eye and together took full responsibility for the waves of individual and collective violence throughout the city (Bezucha, 1974). The term the ‘dangerous classes’ conveniently fused the deepest fears of France’s ruling classes: fears of a criminal class anxious to steal their property and of a lower class anxious to overthrow their political domination(Bezucha, 1874). These hostile feelings were clearly triggered by the lower class activity during the July Revolution and large-scale riots of 1831-1843 (Bezucha, 1974). Social changes such as industrial development, economic change and growing class consciousness of the working class all contributed to the uneasiness that the bourgeoisie felt towards the ‘dangerous classes’.

An illustrated image of Gouette d’Or in Paris from Emile Zola’s novel ‘L’Assommoir’ An typical working class apartment building, though there may have been some middle class occupants on the lower floors.

Haut de la rue Champlain (vue prise à droit) (Top of the rue Champlain) (View to the Right) (twentieth arrondissement) Charles Marville (French, Paris 1813–1879 Paris) Date: 1877–1878 Metropolitan Museum: metmuseum.org/exhibitions/objects?exhibitionId=%7b21968755-5DDD-4FEA-81C5-000D8AAAF6B3%7d&rpp=6O&pg=1

Cours de la Bièvre (Course of the Bièvre River) (fifth arrondissement) Charles Marville (French, Paris 1813–1879 Paris) Date: ca. 1862 Metropolitan Museum: metmuseum.org/exhibitions/objects?exhibitionId=%7b21968755-5DDD-4FEA-81C5-000D8AAAF6B3%7d&rpp=6O&pg=1

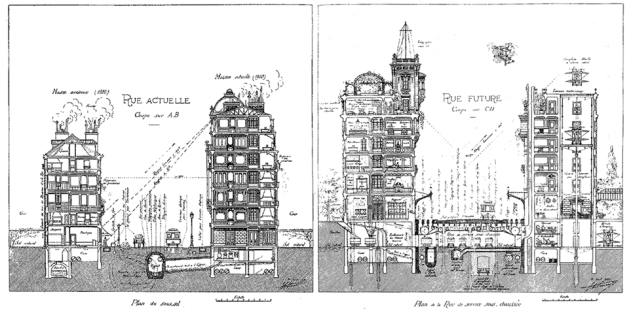

Paris into the 19th Century remained a medieval walled city and such the expanding population had been forced to live within the legal limits of the city demarcated by a wall until 1840; the development of housing and infrastructure was impacted greatly (Taunton, 2009). Available houses were quickly filled; dwellings were then subdivided for multiple families or individuals to inhabit; when this breakup of space became insufficient, upper stories were added to old buildings (Taunton, 2009).

Facilities such as water would be fetched from a single tap in the courtyard or on the landing, the poor building materials and cramped accommodation forced people into contact with their neighbours (Faure, 2006). Flat doors were often left open, though one did not simply walk into a neighbouring room (Faure, 2006). Much effort was devoted to combating the intrusion of outsiders into private life, though conditions were often too poor to spend much time inside the apartments (Faure, 2006).

Place Saint-André-des-Arts (sixth arrondissement) Charles Marville (French, Paris 1813–1879 Paris) Date: 1865–1868 Metropolitan Museum: metmuseum.org/exhibitions/objects?exhibitionId=%7b21968755-5DDD-4FEA-81C5-000D8AAAF6B3%7d&rpp=6O&pg=1

While the working classes found themselves in these cramped conditions, working class neighbourhoods were well spread throughout the city, areas such as Montmartré and Lé Cours de Miracles holding a large number of industrial workers. Such extremely dense working class neighbourhoods Haussmann termed the immeuble (Taunton, 2009). As Haussmann transformed Paris into a modern industrial hub and work of art, he also changed the social relations within the city limits:

“The physical and social transformation that drove the poor out of sight now brought them back directly into everyone’s line of vision. Haussmann in tearing down the old medieval slums, inadvertently broke down the self-enclosed and hermetically sealed world of traditional urban poverty. The boulevards … enable the poor to walk through the holes and out of their ravaged neighbourhoods … And as they see, they are seen … The glitter lights up the rubble, and illuminates the lives of people at whose expense the bright lights shine” (Berman 1982:153 cited from (Taunton, 2009, p. 13))

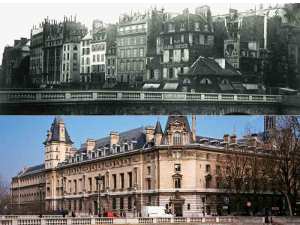

Ile de la Cite before and after Haussmann. Top image taken by Charles Marville. Le Figaro Magazine: http://www.lefigaro.fr/photos/2009/03/27/01013-20090327DIMWWW00367-paris-avant-et-apres-haussmann.php

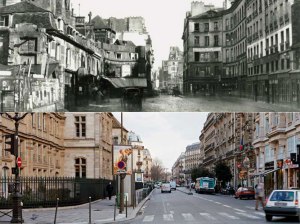

The Court of Miracles before and after Haussmann. Top image by Charles Marville. Le Figaro Magazine: http://www.lefigaro.fr/photos/2009/03/27/01013-20090327DIMWWW00367-paris-avant-et-apres-haussmann.php

Elevation and section view of typical Haussmann apartment building, architectural drawing showing exterior structure. http://quizlet.com/23101469/final-78-flash-cards/

The grand buildings that Haussmann designed framed the new widened boulevards and were more practical for the space, though challenged working class ideas about houses and ‘home’. The new streets now …”made it possible to build more than one apartment facing the street on each floor… façade width increased more along with the depth of buildings; hallways and storage areas … lavatories were … inserted in the core of the construction”… while the advent of a landing allowed one set of stairs to service multiple apartments on each floor of the building (Taunton, 2009, p. 28). Furthermore there was a new trend emerging whereby individuals would retreat into the interior of their homes rather than into the street (Taunton, 2009).

The vision of the old slums being ripped down was captured in Emile Zola’s L’Assommoir …Alongside the tall new houses, many rickety shacks were still standing; between the carved facades there remained blackened gaps where jumbled hovels flaunted their dilapidated windows … the dreadful poverty of the slums forced itself upon the eye”(Zola 1995: 406-7 cited in (Taunton, 2009). The dreadful poverty of Paris was slowly flattened and modern bourgeois Paris was born. In the process many working class Parisians, dangerous or not felt alienated from their surroundings.

Adolphe Alphand, drawing included in his 1867-73 ‘Les Promenades de Paris’, pub. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. Showing a building before (left) and after (right) the Haussmann renovations.

Haussmann altered working class Paris’ way of life within the city of Paris when he demolished large sections of the city and replaced those sections with wide streets and apartment buildings. Paris had become bourgeois in its appearance as well as government; this cemented into the minds of the workers who was in control, and who inevitably controlled their lives.

Sources:

Bezucha, R. J., 1974. Labouring Classes and Dangerous Classes in Paris during the first half of the Nineteenth Century by Louis Chevalier: Frank Jellinek, Journal of Social History, 8(1), pp. 119-124

Faure, A., 2006. Local Life in Working-Class Paris at the End of the Nineteenth Century, Journal of Urban History, Volume 32, pp. 761-772

Mullaney, M. M., 1983. Freiger adn the “Dangerous Classes” Poverty in Orleanist France, Marie International Social Sciences Review, 58(2), pp. 88-92

Taunton, M., 2009. Haussmann’s Paris and the immeuble. In: Fictions of the City: Class, Culture and Mass Housing in London and Paris, http://www.palgraveconnect.com, pp. 7-48